How can a straight knot be untied, which, according to the characteristic unanimously accepted by our experts, is so tightened that it cannot be untied and will have to be cut?” A straight knot, even if wet and tightly tightened, can be untied very simply, in 1-2 seconds.

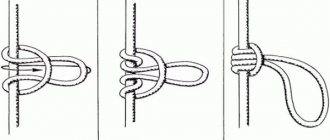

Tie a straight knot as shown in the top diagram of Fig. 25, g.

Take ends

A

and

B

, and ends

C

and

D

. Pull them strongly in different directions and tighten the knot as tightly as possible.

After this, take the root end of A

(to prevent it from slipping out of your hand, make a couple of slings around your palm).

Take running end B

(it can also be wound around your palm).

Pull the ends sharply and firmly in different directions. Without releasing end A from your left hand, clench the remaining part of the knot into your fist with your right hand, holding it with your thumb and forefinger. Root end A

pull to the left - the knot is untied.

The whole secret is that when you jerk ends A

and

B

in different directions, the straight knot turns into two half-bayonets and completely loses all its properties.

It will just as easily come undone if you take root end A

and pull the running end

B

to the left.

Only in this case, end A

must then be pulled to the right, and the rest of the knot (half-pins) - to the left. When untying a straight knot in this way, remember that if you pulled the running end to the right, pull the main end to the left and vice versa.

When untying a straight knot, one should not forget that, with whatever force it was tightened, one of its running ends must be pulled with the same force.

Even a wet straight knot, tied on the thickest plant cable, which was under strong traction (without the brake inserted), can always be untied by taking one of the running ends onto a capstan or winch. In any case, there is no need to cut the cable.

So, the reader now obviously agrees that the characteristic of the direct knot, which has appeared for some unknown reason over the past seventy years in our country, is erroneous. Moreover, it is extremely important for our authors of manuals on maritime practice and rigging to reconsider the interpretation of the very essence of the direct knot and recommendations for its use.

Apparently, only in our country there is an unreasonably respectful attitude towards this unit. Sailors from other countries treat him more soberly and even with prejudice.

For example, not a single foreign manual on knots contains such a dangerous recommendation for a straight knot, which is contained in the “Handbook of Marine Practice” we mentioned: “A straight knot is used to connect two cables of approximately the same thickness.”

The Ashley Book of Knots (New York, 1977), widely known abroad, says the following about the direct knot:

“Previously, this knot had a specific purpose in the fleet - it was used to tie the reef-season sails when they took reefs. Previously, sailors had never used it to tie together two ropes if the latter were of different thickness or make.

It cannot be used to connect two cables that will be subject to strong traction. This knot creeps and is dangerous when it gets wet. After tying the knot, each of its running ends must be secured with a line to the root end.” Elsewhere in his book, Ashley writes: “This knot, used to bind two cables, has claimed more lives than a dozen other knots put together.”

The once famous American sea captain Felix Riesenberg, the author of one of the best textbooks for sailors in English: “Standard Maritime Practice for Merchant Marine Sailors” (New York, 1922) did not speak very enthusiastically about the direct knot.

He wrote: “The reef, or straight, knot, as its name indicates, was used for tying reef seasons... This knot is used in many cases, although it can never be reliable enough if its running ends are not caught. It should not be used for tying ropes for traction. This is a good unit for packing things, packages, etc.”

Unfortunately, many compilers of various manuals and manuals for riggers, builders, firefighters, rock climbers and mountain rescuers still recommend a straight knot for connecting two cables.

Try to tie two nylon cables of “approximately the same thickness” with a straight knot and you will immediately see that even with not very strong traction, this knot does not hold, and if you accidentally pull on one of its running ends, it will certainly lead to tragedy.

And finally, finishing our discussion about the straight knot, we note that the most paradoxical thing here is that the ancient Romans called it a “female knot”, because it was with the “Hercules knot” young Roman women tied the sashes of their tunics on their wedding night. The young husband had to untie this knot. And, according to legend, if he did it quickly, the bride was not in danger of infertility.

Rice. 25. Straight knot

a

- the usual method of knitting;

b -

sea knitting method;

c -

weaving method of knitting;

d -

sea method of untying

the Thieves' Knot

(Fig. 26). At first glance, it is almost no different from a straight knot (see Fig. 25) and it seems that it is akin to it. But if you look closely, it becomes clear that the running ends of the thief's knot come out of it diagonally.

The thief's knot, like the woman's and mother-in-law's knots, are shown for clarity, to emphasize their similarities and differences with the straight knot. It is not recommended to use these four knots, as they are unreliable for connecting two cables.

The origin of the name “thief's knot” is curious. It appeared on English warships at the beginning of the 17th century. The theft of royal property and the theft of personal belongings of sailors on British ships were considered commonplace.

In those years, sailors on warships stored their simple belongings and food, mainly in the form of biscuits, in small canvas bags. Naturally, the bag cannot be locked, it can only be tied. As a rule, sailors tied their personal bags with a straight knot. The thieves, mostly recruits who were not yet accustomed to the starvation ship rations, having stolen other people's biscuits, could not correctly tie the knot with which the bag was tied.

They knitted something similar - a knot that the sailors began to call a thief's knot. There is a second version about the origin of this name: to prove the act of theft from a bag, the owner deliberately tied a knot very similar to a straight one, and the thief, not paying attention to the catch, tied the robbed bag with a straight knot. But be that as it may, the origin of the node, as well as its name, are associated with the fleet.

Rice. 26. Thief's knot

Surgical knot

(Fig. 27). As already described at the beginning of this book, knots have long been used for various purposes not only in maritime affairs, but also in medicine. They are still used by surgeons to tie ligature threads to stop bleeding and to stitch tissue and skin. Nowadays, medicine has not yet abandoned the use of nodes, and doctors skillfully use them.

During abdominal operations, surgeons have to apply sutures made of catgut (a special material obtained from the mucous layer of the intestines of a ram or sheep), which resolves after 3-4 weeks. When tying, the catgut slips, and when making knots on it, surgeons use special clamps.

During microsurgical operations, doctors use extremely thin suture material - a synthetic thread 10-200 times thinner than a human hair. Such a thread can only be tied using special clamps under an operating microscope.

These threads are used when stitching the walls of blood vessels, for example, when replanting fingers, or when stitching individual nerve fibers. Mainly used are woman's, straight, bleached, surgical knots and the so-called “constrictor” knot, which will be discussed later.

When tying a surgical knot, first make two half-knots one after the other with two ends, which are then pulled in different directions. Then another half-knot is tied on top, but in the other direction. The result is a knot very similar to a straight one. The principle of the knot is that the first two half-knots prevent the two ends from moving apart while another half-knot is knitted on top.

This knot is convenient to use when there is a need to tighten and tie some elastic bale or burden with a rope and the tightened first half of the knot on the rope, without letting go of its ends, has to be pressed with your knee.

| Rice. 27. Surgical knot |

Academic node

(Fig. 28). It is very similar to a surgical knot, differing only in that instead of one second half-knot, it has two of them. It differs from its, so to speak, progenitor - the direct knot - in that the running end of the cable is wrapped around the running end of another cable twice, after which the running ends are led towards each other and wrapped around them twice again.

In other words, there are two half-knots at the bottom and two half-knots at the top, but tied in the opposite direction. This gives the academic knot the advantage that when the load on the cable is high, it does not tighten as much as a straight knot and is easier to untie in the usual way.

Rice. 28. Academic node

Flat knot (Fig. 29). The name “flat knot” came into our maritime language from French. It was first introduced into his “Dictionary of Marine Terms” by the famous French shipbuilder Daniel Lascales in 1783.

But the knot was, of course, known to sailors of all countries long before that. We don’t know what it was called before. It has long been considered one of the most reliable knots for tying cables of different thicknesses. They even tied anchor hemp ropes and mooring lines.

Having eight weaves, the flat knot never gets too tight, does not creep, and does not damage the cable, since it does not have sharp bends, and the load on the cables is distributed evenly over the knot. After removing the load on the cable, this knot is easy to untie.

The principle of a flat knot lies in its shape: it is really flat, and this makes it possible to select the cables connected with it on the drums of capstans and windlass, on the ends of which its shape does not interfere with the even placement of subsequent hoses.

In maritime practice, there are two options for tying this knot: a loose knot with its free running ends tacked to the main or half-bayonets at their ends (Fig. 29.a) and without such a tack when the knot is tightened (Fig. 29.b).

A flat knot tied in the first way (in this form it is called a “ Josephine knot ”) on two cables of different thicknesses almost does not change its shape even with very high traction and is easily untied when the load is removed. The second tying method is used for tying thinner cables than anchor and mooring ropes, and of the same or almost the same thickness.

In this case, it is recommended to first tighten the tied flat knot by hand so that it does not twist during a sharp pull. After this, when a load is applied to the connected cable, the knot creeps and twists for some time, but when it stops, it holds firmly. It unties without much effort by shifting the loops covering the root ends.

As already mentioned, a flat knot has eight weaves of cables and it would seem that it can be tied in different ways - there are 28=

256 different options for tying it. But practice shows that not every knot from this number, tied according to the principle of a flat knot (alternating intersection of opposite ends “under and over”), will hold securely.

Ninety percent of them are unreliable, and some are even dangerous for tying ropes intended for heavy pulling. Its principle depends on changing the sequence of intersection of connected cables in a flat knot, and it is enough to change this sequence a little, and the knot acquires other - negative qualities.

In many textbooks and reference books on maritime practice, published in our country and abroad, the flat knot is depicted in different ways and in most cases incorrectly. This happens both due to the negligence of the authors and due to the fault of the graphs, which, when redrawing the diagram of a node from the author’s sketches in one color, cannot always make out whether the end goes above or below the other end.

Here is given one of the best forms of a flat knot, tested and tested in practice. The author deliberately does not present other acceptable variants of this node so as not to distract the reader’s attention and not give him the opportunity to confuse the diagram of this node with any other.

Before using this knot in practice for any important task, you must first remember its diagram exactly and connect the cables exactly according to it without any, even the most minor, deviations. Only in this case will the flat knot serve you faithfully and not let you down.

This marine knot is indispensable for tying two cables (even steel ones, on which significant force will be applied, for example, when pulling out a heavy truck stuck half a wheel in the mud with a tractor).

Rice. 29. Flat knot: a - first knitting method: b - second knitting method

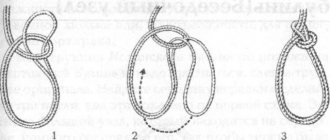

Dagger knot

(Fig. 30). In foreign rigging practice, this knot is considered one of the best knots for connecting two large-diameter plant cables. It is not very complex in its design and is quite compact when tightened.

It is most convenient to tie it if you first lay the running end of the cable in the form of a number “8” on top of the root end. After this, thread the extended running end of the second cable into the loops, passing it under the middle intersection of the figure eight, and bring it above the second intersection of the first cable.

Next, the running end of the second cable must be passed under the root end of the first cable and inserted into the figure eight loop, as indicated by the arrow in the diagram in Fig. 30. When the knot is tightened. the two running ends of both cables stick out in different directions. The dagger knot is easy to untie if you loosen one of the outer loops.

Rice. 30. Dagger knot

“Herbal” knot

(Fig. 31). Despite its name, this elementary unit is quite reliable and can withstand heavy loads. In addition, it can be easily untied in the absence of traction. The principle of the knot is half bayonets with other ends (Fig. 31, i). Sometimes we have to tie two belts or two ribbons, well, let's say, reins. For this purpose, the “grass” knot is very convenient (Fig. 31, b).

It can be tied by slightly changing the “mother-in-law” knot (see Fig. 24) or starting with half bayonets, as shown in the diagram (see Fig. 31, a).

When you tighten the “grass” knot by the root ends, the knot twists and takes on a different shape. When it is completely tightened, the two running ends point in the same direction.

Rice. 31. “Grass” knot: a - the first method of knitting; b - second knitting method

Packet node

(Fig. 32).

Its name suggests that it

is convenient for tying bags and bundles. It is simple, original and designed for quick knitting. The packet knot is somewhat reminiscent of the grass knot. In terms of strength, it is not inferior to the latter.

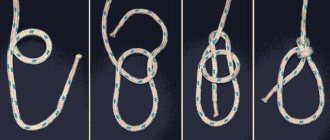

Fisherman's knot (Fig. 33). In Russia, this node has long had three names - forest, fishing and English. In England it is called English, in America - river or waterway junction.

It is a combination of two simple knots tied with the running ends around the alien root ends. To tie two cables with a fisherman's knot, you need to put them towards each other and make a simple knot with one end, and pass the other end through its loop and around the root end of the other cable and also tie a simple knot.

Then you need to move both loops towards each other so that they come together and tighten the knot. The fisherman's knot, despite its simplicity, can be safely used to tie two cables of approximately the same thickness. With a strong pull, it is tightened so tightly that it is practically impossible to untie it. It is widely used by fishermen for tying fishing line (not synthetic) and for attaching leashes to fishing line.

| Rice. 32. Packet node | Rice. 33. Fisherman's knot |

Snake knot

(Fig. 34). This knot is considered one of the most reliable knots for tying synthetic fishing gear. It has quite a lot of weave, is symmetrical and relatively compact when tightened.

With a certain skill, you can even tie the strings of a piano with it. To do this, the place where the string is tied must be thoroughly degreased and coated with shellac.

The snake knot can be successfully used to tie two cables made of any materials when a strong, reliable connection is required.

Weaving knot (Fig. 35). In weaving, there are about two dozen original knots for tying up broken threads of yarn and for connecting new spools.

The main requirements imposed by the specifics of production on each weaving knot are the speed with which it can be tied, and the compactness of the knot, ensuring the free passage of the thread through the machine. Experienced weavers are truly virtuosos at tying their ingenious knots! They tie up a broken thread in just a second.

They have to do this without stopping the machine. Almost all weaving knots are designed primarily for instant tying, so that in the event of a thread breakage, uninterrupted operation of the looms is ensured.

Some of the weaving knots are very similar to sea knots, but differ from the latter in the way they are tied. Several weaving knots have long been borrowed by sailors in their original form and serve them reliably.

The weaving knot shown in Fig. 35, can be called the “sibling” of the clew assembly. The only difference is in the method of tying it and in the fact that the latter is tied into a krengel or into a sail, while the weaving knot is knitted with two cables. The principle of the weaving knot is considered classic. Truly this is the epitome of reliability and simplicity.

| Rice. 34. Snake knot | Rice. 35. Weaving knot |

Versatile knot

(Fig. 36). This knot is similar to a weaving knot in its principle. The only difference is that in a tied knot the running ends point in different directions - this is very important when tying threads of yarn.

It is not inferior in either simplicity or strength to a weaving knot and is just as quickly tied. This knot is also known for the fact that on its basis you can tie the “king of knots” - the bower knot (see Fig. 76).

Rice. 36. Versatile knot

Polish knot

(Fig. 37). It can be recommended for tying thin cables. It is widely used in weaving and is considered a reliable knot.

Rice. 37. Polish knot

Clew knot

(Fig. 38). It got its name from the word “sheet - a tackle that is used to control the sail, stretching it by one lower corner if it is oblique, and at the same time by two if it is straight and suspended from the yard.

The sheets are named after the sail to which they are attached. For example, the fore-sheet and main-sheet are the gear with which the lower sails are set - the foresail and mainsail, respectively.

Mars-sheets serve to set topsails, jib-sheets pull back the clew angle of the jib, and fore-jib-sheets pull back the clew angle of the foresail, etc. In the sailing fleet, this knot was used when it was necessary to tie the tackle into the fire sails in the middle, such as topsail-foil-sheet.

The clew knot is simple and very easy to untie, but it fully justifies its purpose - it securely holds the clew in the sail's crank. Tightening tightly does not damage the cable.

The principle of this unit is that the thin running end passes under the main one and, when pulled, is pressed against it in a loop formed by a thicker cable. When using a clew, you should always remember that it holds securely only when traction is applied to the cable. This knot is knitted almost in the same way as a straight one, but its running end is passed not next to the main one, but under it.

The clew knot is best used for attaching a cable to a finished loop, krengel or thimble. It is not recommended to use a clew knot on a synthetic rope, as it slips and can break out of the loop.

For greater reliability, the clew knot is knitted with a hose. In this case, it is similar to a clew knot; the difference is that its hose is made higher than the loop on the root part of the cable around the splash. The clew knot is a component of some types of woven fishing nets.

Rice. 38. Clew knot

Sea knots. Knots for tying two cables

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In the picture: oak knot.

OAK KNOT. It is used in exceptional cases when there is a need to quickly connect two plant cables. Although connecting the cables with an oak knot is quite reliable, it has a serious drawback: a tightly tightened knot is very difficult to untie, especially if it gets wet. In addition, a cable tied in such a knot has less strength and during operation creates a danger of catching on something during its movement. Its positive qualities are the speed with which it can be tied and its reliability. To connect two cables, their ends need to be folded lengthwise together and, stepping back 15 - 20 cm from the edges, tie both ends as one whole with a simple knot. You cannot tie synthetic cables with this knot - the knot creeps on them.

In the picture: Flemish knot. FLEMISH KNOT. This is one of the oldest maritime knots, which was used on ships to connect two cables - both thin and thick. In fact, this is the same “figure eight”, tied at both ends. There are two ways to knit this knot. The first one is shown in the diagram.

First, a figure eight is made at the end of one of the connected cables. The running end of the second cable is inserted towards the exit of the running end and the “figure eight” tied on the first cable is repeated. After this, grasping each two running ends, left and right, tighten the knot evenly, trying to maintain its shape. For final tightening of the knot, the root ends of the cables are tightened.

The second method: the running ends of the connected cables are laid parallel towards each other so that they touch each other approximately along a length of 1 m. At this point, a figure eight is tied with two folded cables. In this case, you will have to carry it around and thread it into the loop along with the short running end of one of the cables, the long main end of the other. This is precisely the inconvenience of the second method of knitting a Flemish knot.

The connection of two cables with a Flemish knot is considered very strong. This knot, even when tightly tightened, does not damage the cable; it is relatively easy to untie, it does not slip and holds securely.

In the picture: water node.

WATER UNIT. The connection of two cables with a water knot is considered no less strong. It is simple and reliable, but has not found wide use in the navy, because with strong draft it is very tight and it is very difficult to untie it.

In the picture: academic node.

ACADEMIC KNOT. It differs from its “ancestor” - a straight knot - in that the running end of the cable is wrapped around the running end of another cable twice, after which the running ends are led towards each other and wrapped around them twice again. That is, there are two half-knots below and two half-knots on top, but connected in the opposite direction. The advantage of this knot is that when there is a large load on the cable, it does not tighten as much as a straight knot, and it is easier to untie it in the usual way.

In the picture: flat knot.

FLAT KNOT. The name came into our maritime language from French. It was first introduced into his “Dictionary of Marine Terms” by the famous French shipbuilder Daniel Lascalier in 1783. But the knot, of course, was known to sailors of all countries long before that. What it was called before is unknown, but it has long been considered one of the most reliable knots for tying cables of various thicknesses. They even tied anchor hemp ropes and mooring lines.

Having eight weaves, the flat knot never gets too tight, does not creep or spoil the cable, since it does not have sharp bends, and the load on the cables is distributed evenly over the knot. After removing the load on the cable, this knot is easy to untie.

The principle of the flat knot lies in its shape: it is really flat, and this makes it possible to select the cables connected with it on the drums of the capstans and windlass on the valps, which its shape does not disturb, ensuring an equal overlap of subsequent hoses.

In maritime practice, there are two options for tying this knot: a loose knot with its free running ends tacked with half bayonets at their ends (a), or without such a tack when the knot is tightened (b). A flat knot tied in the first way (in this form it is called a “Josephine knot”) on two cables of different thicknesses almost does not change its shape even with very high traction and is easily untied when the load is removed. The second method of knitting is used for tying thinner than anchor ropes and mooring lines, cables, and of the same or almost the same thickness. In this case, it is recommended to first tighten the tied flat knot by hand so that it does not twist during a sharp pull. After that, when a load is applied to the tied cable, the knot creeps and twists for some time, but , having stopped, holds firmly and is untied without much effort by shifting the loops covering the root ends.

Before using this unit in practice, you should remember its diagram exactly and connect the cables exactly according to it, without any, even the most insignificant, deviations. Only in this case will the flat knot serve faithfully and not fail.

In the picture: a dagger knot.

DAGGER KNOT. In foreign rigging practice, this knot is considered one of the best for connecting two large-diameter plant cables. It is not very complicated in design and is compact when tightened. It is most convenient to tie it by first placing the running end of the cable in the form of a number 8 on top of the main one. After this, the extended running end of the second cable must be threaded through the loops, passed under the middle intersection of the figure eight and brought out under the second intersection of the first cable. Next, the running end of the second cable must be passed under the root end of the first cable and inserted into the figure of eight loop, as the arrow in the diagram indicates. When the knot is tightened, the two running ends of both cables stick out in different directions. The dagger knot is not difficult to untie if you loosen one of the outer loops.

In the picture: grass knot. GRASS KNOT (in maritime practice it is more often called “tying with other people’s ends”). This elementary unit is quite reliable and can withstand heavy loads. Easy to untie when there is no traction. The principle of the knot is half bayonets with other ends. It can be tied by slightly changing the “mother-in-law” knot or starting with half bayonets, as shown in the diagram. When the grass knot is completely tightened, the two running ends point in the same direction.

In the picture: fisherman's knot. FISHERMAN'S KNOT. In Russia, this knot has long had three names - “loess”, “fisherman” and “English”. In England it is called “English”, in America - “river” or “vodnitsa”. It is a combination of two simple knots tied with the running ends around the alien root ends. To tie two cables with a fisherman's knot, you need to put them towards each other and make a simple knot at one end, pass the other end through its loop and also tie a simple knot around the root end of the other cable. Then you need to move both loops towards each other so that they come together and tighten the knot.

The fisherman's knot, despite its simplicity, can be safely used to tie two cables of approximately the same thickness. With a strong pull, it is tightened so tightly that it is practically impossible to untie it.

In the picture: snake knot.

SNAKE KNOT. This knot is considered one of the most reliable knots for tying synthetic gear. It has plenty of weave, is symmetrical and, when tightened, quite compact. The snake knot can be successfully used to tie two cables made of different materials when a strong, reliable connection is required.

In the picture: weaving knot.

WEAVING KNOT. Some of the weaving knots (used in weaving) are very similar to sea knots, but differ from them in the way they are knitted. Many weaving knots have long been borrowed by sailors in their original form and serve them reliably. The weaving knot we are considering can be called the “brother” of the clew knot. The difference is only in the method of tying it and in the fact that the latter is tied into a krengel, or into the fire of a sail, while the weaving knot is knitted with two cables. The principle of the weaving knot is considered classic. He is the embodiment of reliability and simplicity.

In the picture: a scalene knot.

VERSATILE UNIT. It is related in its principle to weaving. The only difference is that in a tied knot, the running ends point in different directions. It is not inferior in either simplicity or strength to a weaving knot and is also quickly tied. This knot is also famous for the fact that on its basis you can tie the “king of knots” - the bower knot.

In the picture: Polish knot.

POLISH KNOT. Can be recommended for tying thin cables. It is widely used and is considered a reliable unit.

In the picture: a vine knot.

LIAN KNOT. Although it has not become widespread in the navy, it is one of the original and reliable knots for tying cables. It is unique in that, with a very simple interweaving of each end separately, it holds tightly under strong traction, and is very easily untied after removing the load on the cable - just move any of the loops along the corresponding root end, and the knot will immediately fall apart.

In the picture: clew knot.

CLEAVE KNOT. It got its name from the word “sheet” - the tackle with which the sail is controlled, stretching it by one lower corner, if it is oblique; and at the same time for two, if it is straight and suspended from the yardarm. The sheets are named after the sail into which they are tied. In the sailing fleet, this knot was used when it was necessary to tie the tackle into the fire of the sail with the middle, such as a topsail-foil-sheet. The clew knot is simple and very easy to untie, but it fully justifies its purpose - it securely holds the clew in the sail's fenders. Tightening tightly does not damage the cable.

The principle of tying this knot is that the thin running end passes under the main one and, when pulled, is pressed by it in a loop formed by a thicker cable. When using a clew, you should always remember that it holds securely only when traction is applied to the cable. This knot is knitted almost in the same way as a straight one, but its running end is passed not next to the main one, but under it. A clew knot is best used for attaching a cable to a finished loop, krengel, etc. It is not recommended to use it on a synthetic cable, as it slips and can break out of the loop. For greater reliability, the clew knot is knitted with a hose. In this case, it is similar to a brass knot; the difference is that its hose is made higher than the loop on the root part of the cable around the splash. The clew knot is a component of some woven nets.

In the picture: a bramble knot.

WINDOWLET KNOT. Just like the clew knot, it got its name from the name of the top-sheet gear, which is used to stretch the clew angles of the lower edge of a straight sail when setting the top sails. If the single sheets of the lower sails are tied with a clew knot, then the top clew and boom halyards, boom halyards and boom halyards, as well as the top halyards are tied with a clew knot. The clew knot is more reliable than the clew knot; it does not immediately untie when the pull on the rope stops. It differs from the clew knot in that the loop (or krengel) is surrounded by the running end not once, but twice, and is also passed under the main end twice. The bramble knot is reliable when tying two cables of different thicknesses, and holds well on synthetic cables of equal thickness.

In the picture: a docker node, on the right is another version of the node.

DOCKER NODE. In maritime practice, it often becomes necessary to attach a thinner cable to a thick cable. This need always arises when a ship is moored to a pier (pier), when it is necessary to supply one or several mooring lines from the side. There are several ways to attach the throwing end to a mooring line that does not have a fire, but the most common of them is fastening with a dock knot. To tie this knot, the running end of the thick cable, to which the thin cable is tied, must be folded in half. Insert a thin cable into the resulting loop from below, make one run around the root part of the thick cable and, passing under three hoses, insert it into the loop. The docking knot is strong enough that the throwing end can be used to pull (or lift aboard from the shore) a heavy mooring line, and at the same time it quickly unties. It is better to use it as a temporary node.

In the picture: furrier's knot.

FURRY KNOT. It seems strange that this wonderful knot, long known to furriers, has still remained unnoticed by sailors. His knitting pattern speaks for itself. It is relatively simple, has a sufficient number of crossed ends and is compact. In addition, the furrier's knot has an excellent property: designed for strong traction, it is tightly tightened, but untied without much difficulty. It can be successfully used for tying synthetic cables.

In the picture: hunting knot.

HUNTING KNOT. In our time, inventing a new knot is almost incredible, since at least 500 types have been invented over five thousand years. Therefore, it is no coincidence that the invention of a new knot by the English doctor Edward Hunter in 1979 caused a kind of sensation in maritime circles in many countries. British patent experts, issuing Hunter a patent for his invention, recognized that the unit was indeed new. Moreover, it holds perfectly on all cables, including thin synthetic ones.